Bill Snider still thinks about John Muir a lot.

For most folks, if that name rings a bell, it’s probably ‘You mean the famous naturalist who helped establish Yosemite National Park and other wilderness areas in the U.S.?’

No, not him.

Snider, a product training manager for Dexter Axles, reveres Muir the structural engineer who in 1969 wrote “How to Keep Your Volkswagen Alive, A Manual of Step by Step Procedures for the Complete Idiot,” which Snider read as a teenager and still informs his view on trailer braking today.

“(He said) ‘The ability to stop is more important than the ability to go,’ and he’s more and more like Socrates every time I think about that as I get older,” Snider said. “You’re better off, unfortunately, broke down on the side of the road than you are doing 90 mph toward an object that’s not going to move out of your way.”

In an effort to help trailer manufacturers keep their towing customers from hurtling into an immovable object—and, of course, highlight Dexter’s many products—Snider discussed trailer brakes and more during the opening NATM technical forum “Trailer Brakes and Suspensions for Light & Medium Duty Trailers.”

Snider’s rapid-fire presentation touched on trailer brake laws; trailer brakes types; Dexter design and manufacturing differences; operational and maintenance considerations for trailer brakes; trailer suspensions types; and considerations for suspension loading and alignment.

Brake laws

Trailer brake laws, typically based on gross vehicle weight rating (GVWR) and/or stopping distance, vary widely from state to state and the federal level, making it tricky to track who needs trailer brakes.

In North Carolina, users are required to have brakes on trailers that weigh 1,000 pounds GVWR or more. New York says 1,000 pounds empty, four states start requiring trailer brakes at 1,500 pounds GVWR, most states start at 3,000 pounds GVWR, and Massachusetts is all the way up at 10,000 pounds empty.

Other states fall somewhere in between: Some emphasize stopping distance, and others only stipulate certain types of trailers in their regulations, leaving room for interpretation.

“The engineer in me loves the data,” Snider said. “The problem is: Who actually certifies it?

“I’ve been in the business about 15 years, and as far as a trailer manufacturer selling a trailer in a state where it has to stop in a certain distance, I don’t really see folks who have a lot of certifications in their files.”

Theoretically, a police officer could put a trailer to the test, but who is confirming the real-world results? Is it by certification or enforcement? Snider’s unsure, but he’s certain trailer makers should conduct their own tests, and keep records of stopping distances, even if informal, on file.

Unique trailer brake laws include states that require brakes or safety chains on all trailers (North Dakota), and brakes only on fifth-wheel trailers or HAZMAT trailers weighing more than 3,000 pounds (Missouri).

Colorado, Connecticut and Nebraska have different rules for commercial and personal trailer towing, Connecticut also asks if the towing is for interstate or intrastate purposes, with differing brake requirements.

“There really ought to be a consistent law, and (trailer makers) know that,” Snider said.

Per federal regs, surge brakes now are allowed for commercial/interstate use on trailers up to 12,000 pounds GVWR when towed by a vehicle weighing at least 57.14% of the trailer GVWR. For heavier trailers, weighing between 12,000 pounds and 20,000 pounds GVWR, the towing vehicle must weigh at least 80% of the trailer GVWR.

After figuring out which trailers need brakes and which kind are allowed, the question is, how many?

Some states say if the trailer needs brakes, the brakes must be on every wheel.

Other states say a determination depends on trailer weight, with limits varying wildly from state to state, and the number of axles. Alaska allows a trailer to have one idler axle on a tandem or triple-axle unit.

With so many discrepancies in state laws, Snider suggests a simple solution.

“Bottom line is, we’d like you to put brakes on all the axles,” he said.

Trailer brake types

The options for trailer brakes include electric brakes, surge hydraulic, electrically powered hydraulic brakes and air brakes.

Electric brakes require a tow vehicle controller that, depending on how hard the brake pedal is pressed, output 3-12 volts, actuating the magnets inside a brake drum that has a machined surface for the magnets to stick to, producing a wedging action that works well in stopping the trailer.

Benefits include simple installation and low initial cost.

“The tow vehicle calls for brakes through the controller, it sends about 3.5 amps and at least 10.5 volts for maximum braking, and then that magnet tries to stick itself … and the more voltage you give it the harder it tries to stick itself, and that magnet then slides backward, if the wheels rotate,” Snider said.

Surge brakes are built into the trailer tongue and generate 600 to 1,200 psi, depending on the actuator and application. Disc brakes work best with this system, Snider said, especially if corrosion is an issue, but it’s more complicated to install, requiring hydraulic lines for actuation.

Also, the tow vehicle must stop first, unless the emergency brake is pulled.

However, surge brakes don’t require any wiring, so even if the truck’s electrical connection is bad, the trailer still will have brakes.

Electrically powered hydraulic brakes share many similarities with electric brakes. The drum model features a 1,000-psi working pressure, and the disc model puts out about 1,600 psi. Snider raved about this system but cautioned that the model and brakes must match, and the initial cost is higher.

“This combines both worlds,” Snider said. “You’ve got the electrical controller in the truck, (and) you’ve got a super-fast-operating hydraulic brake pump built into the trailer.

“They do have a higher initial cost … but once you have that on your trailer, you will never go back. They really, really stop well, and you have the independent brake control in the tow vehicle as well.”

Snider says he prefers the disc model, which has reduced maintenance requirements and enhanced performance forward and backward.

“Usually, if people have electrical and hydraulic, they’ll go ahead and put disc brakes on,” he said.

Air brakes (drum or disc) are the preferred option for commercial vehicles because of their superior reliability, but the tow vehicle must have the right compressor and two sets of air lines, and federal regulations require the brakes to include service air, and emergency or parking air systems.

Dexter design differences

Dexter uses only ASTM-certified materials, and boasts stringent engineering and testing, and automated, domestic manufacturing, making their trailer components the best in the industry, Snider said.

The company also is uniquely accredited by the Canadian Standards Association as a self-certifying laboratory.

“We build a lot of our own brakes, and when I say we build them, we build them from scratch,” Snider said. “Albion, IN is where they’re built, we build millions of brakes, and we really like to control what goes into them, and we also like to know exactly what comes out of them.

“And one thing we do that’s different from a lot of folks is, is we do a ton of testing.”

Snider said the company conducts thorough testing to guarantee the dependability and performance of its brake linings—including secure shoe attachment and maximum torquing—backing plates, castings and seals.

Advantages of Dexter’s manufacturing processes include a highly automated, process controlled environment, ISO 9001 certification, a rigorous vendor qualification process and vertical integration.

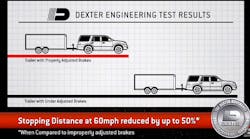

Snider recommends putting brakes on all axles for trailers that need brakes, because they last longer and perform better; but brake type is only one consideration in overall trailer brake performance. Other factors include axle type, suspension and how the trailer is used and maintained.

Trailers should be towed with the frame level, helping to properly distribute the weight across all axles.

“(With) torsion axles, if you tow them tongue-low or tongue-high, the unweighted wheel will be the one most likely to skid at the first sign of needing to brake really quickly,” Snider maintained.

However, if the trailer frame is too flexible, combining the wrong stiffness weight rate and length, the trailer may become “excitable,” creating a harmonic like an out-of-balance tire, so correct trailer frame stiffness is key in avoiding brake chatter or chucking, or oversensitivity to road input.

Dexter also recommends “burnishing,” or breaking in, new brakes.

Drum shoes come with a cam-shaped profile when new, and then the shoes wear in to fit the drum perfectly. But initially the shoes contact the drum in the center of the shoe, so they require burnishing.

Manufacturers can tell buyers to brandish the brakes or do it themselves, perhaps during delivery.

“We like to see 20 of these decelerations … before we say, ‘OK that brake is really ready, solid, and it’s going to get its rating,’” Snider said.

Readjustment is recommended at the first 200 miles, if the brakes aren’t self-adjusting, as with Dexter’s Nev-R-Adjust electric brakes. Manually adjusted brakes should receive service every 3,000 miles.

Trailer suspension types

Dexter’s trailer suspension options include leaf spring, torsion (TorFlex), hybrid (AirFlex), heavy duty (HDSS) and air ride.

Leaf spring suspension axles are the most familiar. They range in capacity from 2,000 pounds to 27,500 pounds and come in single, tandem and triple-axle varieties, and double-eye or slipper. They’re the most affordable option for improving ride quality, and they’re customizable, with straight and drop spindles, over/under slung springs and hangers used to obtain different trailer heights.

Torsion axles are a newer and popular option, Snider said.

Dexter’s TorFlex is a rubber-cushioned torsion suspension axle that produces a smoother, quiet ride, with less transfer of road shock, insulating cargo from shock and vibration. In addition, multiple arm angles and frame brackets, and fixed and removable spindle/arms, allow for trailer design flexibility.

“It rides really well, it’s quiet, and it’s got the rubber rods that absorb the shock,” Snider said.

Torflex suspensions range from 600-pound to 12,000-pound axle capacities, and require less installation labor, making them a more cost-effective option than many manufactures might think.

“A lot of folks like the torsion because it bolts solidly into the trailer frame and you get a cross member out of it,” Snider said.

Dexter’s hybrid Airflex air-ride suspension has rubber that cushions the ride if air is unavailable. They come in single-, tandem- and triple-axle configurations, and options include a ride height control valve and air-generation kit. They also boast an internal alignment adjustment system.

“It’s a torsion axle that’s mounted in an air-bag suspension,” Snider said. “They’re available in 7,000 to 10,000 pounds, and folks who use these usually have some kind of precious cargo or a really high-end RV they want to ride really well, and boy these things ride well because you’ve got double cushion.”

HDDS suspension systems are designed for heavy-duty spring axles but can be used with medium-duty axles. They feature extended-life equalizer bushings for reduced maintenance effort and cost, adjustable trailing rods for reducing dog-tracking, and axle spacing versions from 49 inches to 60 inches.

Suspension considerations

In axle suspension applications that utilize leaf springs or torsion axles, axle spacing is a key consideration in ride quality. Typical spacing ranges from 33½ inches to 36 inches for a light-duty trailer, 38 inches to 48½ inches for a medium-duty trailer, and 49 inches to 60 inches for heavy duty.

Spreading the axles improves anti-sway, but it also makes assuring level towing more important, and ensuring proper hitch weight and load distribution between axles more difficult, increasing the chance of frame stress concentrations and poor harmonics, particularly with torsions.

Lightweighting is a top priority for manufacturers, but using a steel gauge that’s too thin leaves the trailer susceptible to flexing. And if the metal is welded incorrectly and the metal shrinks, the trailer bows, making it impossible to level and often leading to loads twisting with the frame.

“If you’ve got one that’s got a nice banana in the frame, and the front or rear axle is overloaded, that’ll drive you nuts,” Snider said.

Other considerations include dissimilar metal connections, like aluminum bolted to steel, which leave fasteners susceptible to fretting and galvanic corrosion; tongue weight, a factor in trailer sway if the trailer is unevenly loaded front to back; suspension equalizing, with different options for triple axles; and axle rating/camber versus load, particularly when using bias tires on a trailer.

Snider recommends using radial tires, which are more forgiving of positive/negative camber.

“Some folks buy a 3,750-pound axle and use it for every trailer they’ve got,” he said. “If they need two, they put two on. But if you take a 3,750-pound axle and you put a 1,500-pound trailer on top of it, and use bias ply tires, it’s going to go down the road like this (dog-tracking), and they’re going to wear.

“So that’s a consideration for how you set your trailers up,” he said. “Try to consider the nationwide customer base when you’re designing and choosing your trailer brakes.”