Parts managers must measure everything they do, because they can't improve what they can't or don't measure

KEITH Ely, general manager of Keith Ely & Associates, has worked with over 300 dealerships/branches, manufacturers, and associations in an advisory or classroom setting, on issues involving trailers, heavy trucks, and heavy equipment.

He believes parts departments can radically improve performance through the service department — a natural leader in increasing parts sales.

“The more labor we can sell, the more parts we can sell,” he said. “Also, the better our fill rate to our service department, the more opportunity we have to sell labor. The service department is the one department where, based on one dollar's worth of labor sales, we can actually have more than one dollar of gross profit when we sell parts and labor combined.”

In a National Trailer Dealers Association webinar, “Improving Parts Department Performance Through Inventory Integrity,” he outlined methods to improve parts inventory performance, service department performance, and customer relationships.

He said “inventory integrity” means the inventory that is represented on a company's computer system is correct. The right amount of parts is on-hand for demand (increasing the fill rate) and the amount of on-hand inventory is lowered.

“As parts managers, we recognize that that's maybe sometimes a bit of a conundrum,” he said. “The cost per transaction must be lowered, which provides pricing flexibility. There should be an increased return on inventory. As advisers, we believe that the investment that any business owner makes — in this case in inventory — deserves a certain return.

He said parts managers must measure everything they do, because they cannot improve what they cannot or do not measure.

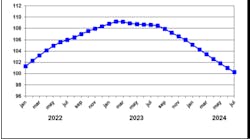

Performance excellence can be measured by gross return on parts inventory investment, which is annualized parts department gross profit dollars divided by parts inventory dollars (including dirty cores).

“From research we've done through NTDA and elsewhere, that performance guide is 250%,” he said. “For every dollar of inventory, that inventory produces $2.50 of gross profit.”

The gross return on parts inventory investment is determined by pricing, which is typically driven by the market and also driven by how parts managers manipulate their computer system to adjust pricing so certain parts are priced in different ways than other parts; and by the fill rate, which is how much a parts department can fill on the first request from inventory. If a technician or customer asks for it, and it can be filled, that's a first-time fill rate. If the parts manager has to go down the street to obtain the part, or the part is a lost sale, that's not a first-time fill rate.

Parts economic profit is annualized parts net income minus the minimum investment percent return (50%), multiplied by parts inventory and parts receivables.

“The net income of a parts department needs to exceed that cost of inventory and parts receivables,” he said. “Getting the parts inventory to turn quickly is the single most important part of getting a very strong return on investment. Gross profit improves, but turns and fill rate are by far the most important pieces.”

Scary statistic

True turns are sales from stock annualized divided by parts inventory. Sales from stock equal the cost of sales minus customer orders minus emergency purchases. It's a measure of turns based on sales from stock.

“Our guide is five turns a year,” Ely said. “It's having the right parts on hand but not having too many of them.

“The probability of selling a part that's more than nine months old is only 15%. For a parts manager, that is a pretty scary statistic. That doesn't include seasonal items. As we're talking about aging and moving parts out of inventory, the idea is to move parts out when they reach nine months or older.”

The fill-rate calculation is done by pieces, not dollars. It is the sales from stock divided by total demand. (Sales from stock equal total pieces sold minus customer order pieces minus emergency purchases pieces. Total demand equals total pieces sold plus lost-sale transactions.)

“The guide is an 85%-plus range,” he said. “But that depends on your sales mix. If you're doing a lot of trailer repair or rebuild, that number will not be that high.”

It's always a balancing act in terms of having inventory to meet demand versus idle capital/excess inventory.

“You have to know what the demand is and be able to predict what it will be and know how much to have on hand without overstocking,” he said. “I've seen where an owner will say, ‘I don't want you to have over X-dollars in parts inventory, but I also don't want you to lose any sales.’ That becomes a very, very difficult balancing act. We have to understand it and know how to solve it.”

There are no “pros” to outweigh the “cons” of idle capital, he said.

“That's money that's sitting on the shelf,” he said. “That's cash that could be better utilized by the branch.

Idle capital is: excess inventory, where on-hand quantity is greater than the “best stocking level”; obsolescence, which is measured by over seven months of no sales; forced stock, which has never met the phase-in criteria, yet forced into stock (special orders not picked up by customer and put into stock; technician/service advisor speculation; wholesale returns; and speculative parts stocking).

“Most excess inventory is not over-purchasing — it's slow demand,” he said. “That is something most parts managers don't understand. They don't understand the criteria. We have seasonal and high-dollar parts not sourced correctly; significant variances in minimum and maximum; and lost sales not recorded accurately. This has more of an impact on the performance of a parts department than probably any other item. Somehow we have to capture the lost sales. A lost sale is simply if a part is requested is out of inventory and we can't fill it, and it is not ordered.”

He said technical obsolescence — in which the part number is good, but there's between seven and 12 months with no movement — is typically caused by forced stocking due to special orders, poor tracking of demand, or phase-in/phase-out not being set up correctly.

“Forced stock is almost all from special orders,” Ely said. “A part ‘forced’ into stock has very little chance of selling again — about 35%. Of the 35% that do sell, 80% sell to the same customer who ordered in the first place.

“The average branch has 25% of inventory tied up in forced stock. That is special orders that either have not been delivered to the customer, sold to customer, or, if the customer has not picked them up, they have not been returned to the manufacturer. If you're not requiring a deposit on the customer-paid part, I would encourage you to do that.”

Standards to strive for

• Performance Excellence Standard #1: Become familiar with the parts inventory management report.

Key things to look at on the report: inventory balance (active, non-stock, manual order, auto phase-out, no cost, negative on-hands, and core/exchange); inventory movement (sales and receipts); and receipted orders (stock orders, customer orders, and emergency orders).

“We want to maximize the use of stock orders, because typically that's free freight and we get return privileges, which we don't get off customer orders and emergency orders,” he said.

• Performance Excellence Standard #2: Perform a physical parts inventory annually.

“Most parts managers look at it as a necessary evil — something they need to do because their CPA tells them to,” he said. “But it's is an excellent opportunity to verify the physical count and value of the parts inventory and reconcile inventory against the general ledger. You should assess inventory-management performance. ‘When we do our plus-minus report, how many pieces were we off? Do we have parts in the wrong locations?’ Even though the dollar amount may not be that far off, we may have parts numbers with incorrect counts in the system.

“When used as a management tool, physical inventory can lead to significantly improved inventory performance and fewer differences between the physical value and the general ledger value in the future, along with an increase in turns (gross and true) and fill rate.”

• Performance Excellence Standard #3: Inventory-management practice implementation.

“It's very labor-intensive and a discipline — something you have to measure, observe, and enforce every day,” he said. “If it's not done, you won't get the results you should. We've seen a fill rate in the 80% area pushing up to the 90% range while actually lowering the parts inventory.

“Three items key to having high turns and high fill rate are on-hand accuracy; outside purchases made from a special-order basis from a factory or from another vendor or trailer distributor; and lost sales.

“If we're not recording them, we're missing a large piece of tracking,” he said.

He said monthly reconciliation between accounting and physical inventory is “very difficult to do because there are a lot of moving parts, with packing slips and returns you've made, and dirty cores. But it allows you to see when there may be a problem occurring between accounting and the physical inventory. We want to fix that as soon as can.

”Outside purchases have to be accounted for accurately. One of the best practices you can do as a parts manager is review lost sales — not just record them, but understand why. Is it a part we never had demand for or just out of stock on? Same for outside purchases. For a purchase on a special order from our manufacturer or an order through another distributor, record it, but more importantly, ‘Why did we order the part and what do we do to fix it?’ You may find that order points are set up incorrectly on the system, that this part should have been phased in.”

Bin checks/perpetual inventory must be done daily, he said. If there are no-bin-location parts, the parts manager needs to determine why they're not in a bin location and then assign them a location. On out-of-stock parts: Are they qualified for stocking status and there are zero on hand? The manager needs to verify that they are out of stock and determine what needs to be done to correct it.

“Each bin should be counted on average three to four times per year,” he said. “It's difficult to get this done, especially in a smaller department. We're looking for, ‘Did we sell a left piece rather than a right piece?’ We're looking for variances in our counts and bin locations, for things that caused the inventory to be incorrect.”

The manager should identify a set of bins that can be used for forced stock, setting up three sources for forced stock: retail forced stock; wholesale forced stock; and speculative inventory. Comment fields should be used to track parts coming back into stock.

Ways to control excess inventory: isolate seasonal parts into separate sources and monitor the sources closely; isolate high-dollar excess inventory into separate sources and exclude from regular stock orders; monitor sales, on-hand, maximum; reduce variance between minimum and maximum; and monitor lost sales reports daily.

All plus/minus adjustments need to be verified daily. The totals need to be given to accounting at the end of the month, with the cost of adjustments (plus or minus).

“Inventory pricing adjustments — price tape — must be accounted for monthly on the general ledger,” he said. “Special order parts must be managed appropriately. Returns must be used to the fullest capacity. There needs to be proper vendor return accounting on parts returns and core returns. Maximize use of stock orders. Reconcile lost and customer/emergency purchases as to ‘why.’”

He said phase-in/phase-out means that “it takes so many demands in a certain period of time for a part to come into the system. A demand could be a sale or lost sale. Look at the settings in system, and analyze by source, by type, and by vendor. You will have some parts you want to bring in quicker — smaller parts, parts going more to the service department, parts that would cause a trailer to be down. We want those parts to come in quicker, so that instead of having three demands in two months, we do it in two demands in 12 months.”

He said economic order quantity is based on discounts and the cost of the part versus the handling cost of the part.

“Even though we may have an O-ring that costs 10 cents and sell it once a month, it probably makes no sense to order two O-rings at a time because the cost of handling that piece is so much more than the cost of holding that part.”

• Performance Excellence Standard #4: Cores, the parts that are going to be rebuilt, must be managed correctly.

“Good core management begins with treating every core like a new part,” he said. “Inventory must be kept accurate. We need to know at every point at every day what our dirty core inventory is. Returns must be made timely. We can't have any obsolete cores that have exceeded return time to vendor.

“Put a clean core into inventory. Bill out the core as separate line item on an invoice. Credit the core to a customer when the core turned back in. It doesn't matter who the customer is. You have to track the core and only credit them when they turn the dirty core back in. Identify the dirty core, place it into inventory, send dirty cores back for credit to the supplier, bill the supplier for the dirty cores, and track the dirty cores receivable.”